Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America by Aby Warburg

Marcelo Guimarães Lima

Marcelo Guimaraes Lima

review of

Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians

of North America by Aby Warburg

The Psychohistory Review

volume 25, number 2

Winter 1997

University of Illinois at Springfield

Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America.

Aby M. Warburg.

Translated with an interpretive essay by Michael P. Steinberg.

Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America is a transcript of a 1923 lecture given by Aby Warburg in the Kreuzlingen Sanatorium where the author was a patient of Ludwig Binswanger. As the prefatory note to the present edition explains, Warburg did not consider the text publishable and restricted its access to a few friends and collaborators, among them the philosopher Ernst Cassirer. The text came to light, however, in 1938, nine years after Warburg’s death, in an abbreviated English translation in the Journal of the Warburg Institute in London; in 1988 the full German text was published. The present American edition is a complete translation by Michael P. Steinberg with an essay by the translator that equals the length of the text itself.

The career and personality of Warburg—art historian, researcher, and collector of books and manuscripts related to the art and culture of the Renaissance—marked the development of the modern discipline of European art history in the first part of the present century. Not only did Warburg assign art history the role of a central discipline for understanding human cultural development, he was also an intellectual leader to a generation of young scholars. His private collection, generously open to researchers and students of classic culture, was the seed of thepresent day Warburg Institute.

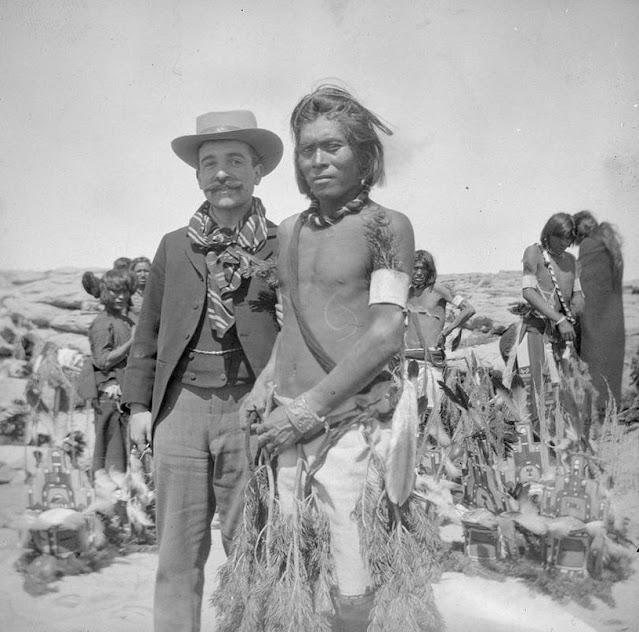

The biography of a rich and complex personality such as Warburg has elements of dramatic and narrative interest and brings to mind characters and something of the dramatic atmosphere of the literary universe of, for instance, a Thomas Mann. Warburg was a German-Jewish intellectual, a European scholar at the turn of the century and the heir of one of the most traditional and wealthy financial houses in Europe. Unfortunately, his intellectual tenacity and courage were coupled with a psychological instability that led him to a period of treatment at Kreuzlingen. Among other things, Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians is a document of Warburg’s life: a retrospective narrative of his visit to New Mexico in 1896-1897—elaborated more than 20 years later, at a particularly crucial moment of struggles for his mental integrity. And, herein lies part of its interest.

More important, perhaps, this work, according to E. Gombrich in his intellectual biography of Warburg is the most explicit statement of Warburg’s intellectual project. His central thesis and guiding concept is presented in this short piece in a language far from clear; it bears the marks, we could observe, of the effort of a conceptual world in statu nascendi.

In Gombrich’s words, the notes for the lecture on the Serpent Ritual of the Hopi are “couched in an almost private terminology that presents insurmountable obstacles to the translator” (and perhaps to the readers also), and yet they also present “the most explicit formulation of Warburg’s general ideas.” With his observation, Gombrich gives us the paradox of an intellectual work of systematic and universal ambition whose theoretical center is at its most opaque and least structured—literally its most embattled part. The particular circumstances of the conception of Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians, no doubt, have something to do with it: the work marked to Warburg himself the end of his critical period at the mental institution, and it was a self- imposed test of recovery and return to productive life. Circumstances, however, can never thoroughly account for texts. What is left after we consider the aspects of the text’s identity and its circumstances are the text’s “internal” and “external” differences.

In the case of Warburg, “wild” ethnography, classical scholarship, and philosophical speculation go hand in hand to produce and present the central focus of his analysis of Hopi mythology and religious ceremonies. The Hopi dance with live serpents at the villages of Oraibi - and Walpi is the occasion for an iconography and an iconological investigation. The evolution of the pagan religious world from magic cult to spirituality, from blood sacrifice to symbolic transformation, is mapped by the art historian’s gaze in the gallery of images from the Ancient to Hellenistic World (The Laocoon group), from the Roman through the Christian Medieval World to that era of transition—the Renaissance—in which Classical Paganism fashions a new view of the present and the future inside a Christian culture in the process of transformation and secularization.

The serpent itself in this process is transformed from creature of death and destruction into the symbol of a return from the underworld, of immortality and renewal. It is the duality that becomes manifest—of the serpent-god as evil or benefactor and protector—that the Greek world conceived in the scepter of Asclepious, the god of healing. That, in turn, passes into the Christian World as an astrological symbol.

To Warburg, the reconstruction of paganism in the New Mexican desert is a chapter on the mapping of the evolution of symbols and the symbolic domination of the world by man that anticipates modern science (a conception akin to Cassirer’s epistemological investigations of mythical thought and symbolism). It is, however, also the “‘archeological” investigation of deep psychological strata of the human mind. Warburg believed the Pueblo Indians are the survival of Humanity’s former self, and in this sense they are perhaps closer to ourselves than we can at first imagine. Modern European civilization, conscious of its beginnings in the Greek World, has nonetheless, according to Warburg, lost sight of the “kinship of Athens and Oraibi”: Oraibi itself becomes the new key for understanding Athens, the Classical World, and the Revival of Pagan Classicism in the Renaissance. And, crucially, it is also the key for understanding the Dionysian center of Greek culture and classic culture in general—of the tensions and polarities that have marked not only humanity’s cultural development but that are active as inner-structural forces at the core of modern Western Culture itself.

By tracing origins and function of the rebirth, or the reinvention, of paganism in the Renaissance—the central project of his developed program of iconological investigations—Warburg aimed at disclosing inner-spiritual conflicts, contradictions, and compromises. They are better seen or apprehended during times of historical transitions that form the very stuff of art and the inner core of the classic ideal: the formal resolution of inner struggles of the human spirit that nonetheless conserves the polarities and the energies of conflict within the attained form of the Beautiful, the classic work of art itself. To Warburg, Renaissance Paganism was at the same time a tool for overcoming the Medieval heritage and the very stuff of a much older “tradition,” one that pointed to a regressive experience of the self toward more primitive forms of consciousness and forms of life, toward the “other,” darker side of the human spirit, to the bondage of fear and superstition.

The conflict between civilization and “barbaric” humanity witnessed in New Mexico amplified Warburg’s perception of the anxieties of historical transitions and cultural change as well as the paradoxical “irresolution” of man’s spiritual conflicts despite transformations of historical forms of life. It also pointed to the functions of the Symbolic Image as a bridge between the inner and the outer world and as the receptor and transmitter of spiritual tensions within and between cultures and epochs. To Warburg, myth and symbols constitute history’s “other’—the reverse side, which accompanies history as its necessary complement, the “other half’ whose contrast illuminates the apparent side.

To modern man, observes Warburg, the animist, fetishist, religious propitiatory practices of the Pueblo Indians represent a curious melange of the mystical and the practical, of magic as a technique for survival and as an early form of spirituality. What may represent for us the marks of a mental split is for the natives, however, “a liberating experience of the boundless communicability between man and the environment.” That unity of man and nature, of all the living, is what we may call a “cosmos.” And yet, the serpent, symbol of suffering and redemption, must die and pass as the mythical world itself. In the last illustration of the lecture, “Uncle Sam,” the anonymous passerby, with his top hat and beard, strolls on a street in San Francisco, seen by Warburg among the lamp posts, electric cables, and neoclassic architecture. Far from New Mexico and its ancient peoples, all is apparently clarity and order in the urban civilization of White America. And yet, Warburg points out, modern technology cannot by itself generate or regenerate the lost “cosmos”; the unity it promotes in the universe, the bridging of distances, the taming of the forces of nature, is in fact the desolation of beings, the undoing of the communicative order.

Historicism, Frederic Jameson once observed, is that experience of the “otherness” of the past that intends to restore to the subject the totality of the infinite potentialities, the manifold of the human spirit, in all its richness and actuality of forms, and, therefore, transcends the alienation that afflicts the subject as the transience and the blindness of the present, of what is felt and lived as a divided, restricted, and disorganized present. It is essentially, in this sense, an aesthetic experience and, we should add, in central ways a therapeutical one. And as such, the historicist’s experience is also built upon the ideological misconstructions of self and other and of their relations, of the “exalted” and “unexpected” encounters and discoveries that ignore the subject’s active construction—the production of the “historical” object as the (unconscious) object of desire. Perhaps, as Jameson reminds us, the methodological shortcomings, the refined naiveté, and the practical illusions of Historicism and Cultural Historicism as systems and cultural practices are not what should occupy our attention, given also our theoretical (via structuralism and post-structuralism) and historical distance from it. Rather, it is the cultural historicist’s dilemma (which is not his dilemma alone), or his decision on the dilemma of a relation to the other, epoch and/or culture, that does not destroy or falsify the “truth” that was once possessed, that is, his struggles for “authenticity” as the privileged mode of true historical knowledge that will remind us that more may be at stake in history than the endless succession of tropes or the wanderings of signifiers.

The relation to the past and to the other(s), Walter Benjamin insisted, implies care, the result of an active awareness of the potential for destruction, for the loss of identity and of the resources of memory, given in the present. As Benjamin wrote, defining the risks of the cultural war against fascism in the 1930s, not even the dead will be safe if the enemy wins. This sense of the urgency of history, of the need to save the past, that is, to save the future and to save the dead—for theyare also vulnerable and unprotected against their living enemies—is perhaps the “authentic” part of the legacy of historicism. And, this need confronts humanity again and again in times of transition, and it confronts us today, not in the same form but with comparable urgency, for, as Benjamin noted, a common bond and destiny unites the defeated, the oppressed of yesterday with those of today and tomorrow.

We can observe that a specific “urgency of history” also informed some of the most crucial parts of Warburg’s art-historical quest and explains, in great part, his passionate rejection of the comforts of formalism. In his interpretive essay Steinberg focused on Warburg’s own critical, embattled relationship with his Jewish cultural and religious traditions and identity as one of the keys for reading Warburg’s late account of his encounter with the Native-American world. According to Steinberg, the images of the oppressed and discriminated European-Jewish populations that Warburg kept in his study files can be juxtaposed to, reflected by, and reflect in their turn, the images of the conquered and dispossessed Native Americans of New Mexico. The mounting threat of fascism in Europe also links the reflection on paganism (as in the episode of Warburg’s brief encounter with the followers of Mussolini in the streets of Rome) with the more private reflection on the fate of the Jews in Germany. Unfortunately, Steinberg’s “symptomatic” reading is not complemented by a more thorough and articulated examination of the theoretical questions. Specifically, the theoretical difficulties of Warburg’s essay would contribute to a deeper understanding and clarification of the politics of art historical theory itself and illuminate Warburg’s own “Nietzschean” philosophy of culture, as well as illuminate in a more complete, richer way Warburg’s psychological motives and processes, the very focus of Steinberg’s reading.

Silvia Ferretti observed that Warburg interpreted art history as “the history of battles never totally won.” But are “battles never totally won” never totally lost also? Or, do they refer to the recurrence of defeat? For Benjamin, history from the side of the defeated implied the “messianic” hope of historical salvation as a lucid (“utopian” and “disillusioned” at the same time) aspect of his Marxism. Could we conceive, also, something like an “art history from the side of the defeated”?

Benjamin’s writings certainly do contain elements of such an enterprise. Could we also identify similar elements or materials in Warburg’s work? The answer to this question will bring us back to the inventory of Historicism alluded to by Jameson and will require a more sustained investigation of the origins of the modern discipline of art history and the role of Warburg in its development.

Marcelo Guimaraes Lima

University of Illinois at Springfield

Works Cited

Jameson, Frederic. “Marxism and Historicism” in The Ideologies of Theory,

Essays 1971-1986, Volume 2: The Syntax of History, Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

Ferretti, Silvia. Cassirer Panofsky and Warburg—Symbol, Art and History,

trans. Richard Pierce, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1989.

https://archive.org/details/aby-warburg-images-of-the-pueblo-indians

Comments

Post a Comment