Cannibalism and Identity

Marcelo Guimaraes Lima

New Art Examiner, Chicago, June 1999

As the historical section of the 24th Bienal de São Paulo, which ended last December, paid homage to Antropofagia (the Anthropology of Cannibalism), it was able to develop a global forum that examined and responded historically, comparatively, and critically to some of the main questions addressed by early Brazilian avant-garde artists. In doing so, it contributed to the expansion of our understanding of the cultural meaning(s) and critical dynamics surrounding the notion of Antropofagia, while also impacting the Bienal’s exhibition of Brazilian and international contemporary art.

A further examination of Antropofagia raises a number of philosophical problems concerning an understanding of the cultural and artistic “self” and “other,” and the history of the Brazilian avant- garde since the 1920s. “I am only interested in what is not mine. Law of man. Law of the cannibal” proclaims the Manifesto da Antropofagia (Anthropophagic Manifesto)” written by Oswald de Andrade in 1928. The phrase summarizes the complexity of the artist-cannibal self-productive process, one of the central issues, if not the central subject, of Andrade’s poetical / philosophical / critical / ideological intervention in the context of the construction of a Modernist poetics and avant-garde artistic praxis in Brazilian arts in the early decades of the twentieth century. Andrade’s “Manifesto” intended to explore and define the identity of Brazilian Modern art and Modern culture in the late 1920s elaborating both a theory and a program for the avant-garde.

Of the many paradoxes that Andrade’s ironic consciousness was able to point out regarding the situation of Brazilian art, and Brazilian Modern art specifically, the heritage of a “colonial” cultural context was a central question. In such a context, the arts reproduced metropolitan models and ideas and therefore provided artists with an underlying sense of their own inadequacy and subordinated status. In the '20s, the Brazilian avant-garde’s embrace of the new European artistic manifestations such as Futurism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Dada could be viewed in the same light, as yet another reproduction of the “centuries old" colonial frame of mind.

Andrade’s answer to this problem was precisely the analysis and re-elaboration of the exchange processes between the New World and the Old, but placed under the problematizing category / concept / metaphor of cannibalism. The violent image of the cannibal fused, at the symbolic level, the past and the future, through irony elevated to critical method.

The ritual cannibalistic practices of Brazilian natives were described, not without misconceptions and at times serving directly the ideology of conquest, in a relatively extensive literature of exploration, voyages, and contacts since the sixteenth century. One of the earliest descriptions of cannibalism by Brazilian natives was the narrative work by Hans Staden published in Marburg in 1557. Made captive for a number of years by a Tupinamba group, Staden, a German seaman, was spared from sacrifice due to his cowardly behavior. In contrast to the behavior of indigenous prisoners of war, Staden's constant weeping and begging for his life made him unworthy of being eaten.

whose Inhabitants are Savage, Naked,

Very Godless and Cruel Man-Eaters

by Hans Staden, Marburg, 1557

The ritual, “symbolic” cannibalism (in contrast to mere alimentary) by the Brazilian natives provided a “model” for the relationship between self and other that implies the consciousness of conflict and destruction, and the notion of an active renewal of energies by the absorption of the enemy's strength and power, This dialectical “celebration of the other” is a sort of literal embodiment of the Hegelian notion of Aufhebung, or “overcoming,” which is at the same time concealment and preservation of the conflictive relationship. Transposed to the intercultural relationship, the notion of cannibalism provides a more complex image and a deeper understanding of the complexity of the relationships between “metropolitan” and “colonial” cultures or the dominant and the dominated. It also discards the “purist” or isolationist view of the “national-cultural identity” question in the arts (the “rejection of the foreigner”). Against the fear of the enemy or other, the “Manifesto da Antropofagia” proposes to cannibalize it: devouring the enemy, absorbing the other as nourishment, destroy (or deconstruct) it and use the energies thus liberated to invigorate the self, On a cultural level, the power of the dominator must be conquered by the dominated in a process of cannibalistic absorption.

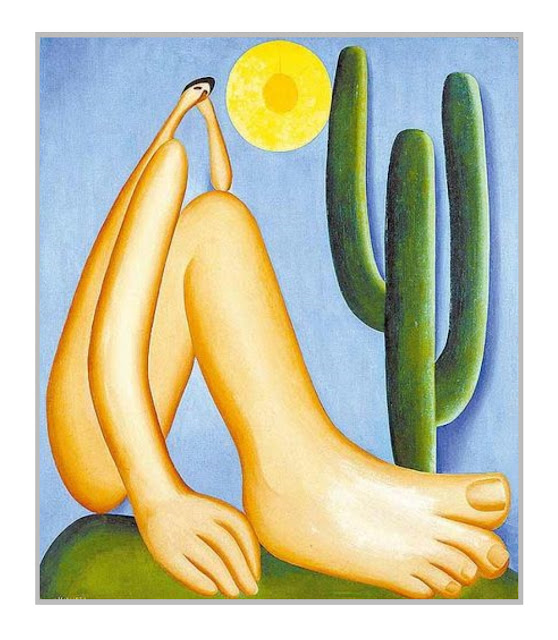

As an artistic movement, codified and proclaimed by Andrade's manifesto, Antrapofagia was a short-lived experiment, both for the author and for the painter Tarsila do Amaral whose works of the late 1920s such as the celebrated “Abaporu”, painted in 1928, anticipated and embodied the spirit of Antropofagia in the visual arts. By contrast, the idea of Antropofagia as cultural / artistic praxis would have a decisive impact in the self-understanding of Brazilian art in the twentieth century.

The

political and economic upheavals of the 1930s, the revolutionary

decade in Brazil, brought an end to the experimental phase of the

Brazilian avant-garde and saw at the same time both the political

radicalization of artists and the beginnings of a process of

codification of the nationalist aspirations of the Modernists into

art forms of a public, and even “official” character and mass

appeal that would culminate, for instance, in the muralism of

Portinari and was also reflected in the beginnings of Modern

Brazilian architecture. To Andrade, as to other artists, left- wing

political militancy was for a while the only possible dialectical

Aufhebung of the avant-garde and in a certain sense, it can be seen

as a sort of continuation (not without contradictions, conflicts, and

misunderstandings) of the ideological aspirations and the cultural

praxis of the avant-garde “by other means."

If the idea of a Brazilian Modernity inaugurated by the young Modernist artists and writersof the 1920s became a “material force” in the 1940s and 1950s with industrialization, social modernization, and the expansion of capitalism, it was also in the process somewhat artistically and ideologically reified. The crisis. of nationalism, that is, of nationalist aspirations within the context of dependent capitalism and subordinate development that already showed its signs in the 1950s, was finally “resolved” by the military coup of 1964. The military dictatorship that would dominate Brazil for the next 20 years made the American Cold War Doctrine its official ideology and ruled the country in many ways as a truly occupational force, imposing its exclusionary model of dependent development and cutting short the Brazilian democratic interval (comprising, after the end of the Vargas dictatorship, the last part of the 1940's, the ‘50s, and the early part of the ‘60s, roughly speaking) of the post-Second World War period.

In Brazilian arts and culture that democratic period was also a period of evaluation of the Modernist heritage and the reformulation and expansion of the notion of the national culture, primarily because it took into account the popular experience and the perspectives of the rural and urban working classes. Also, as the period of development and expansion of a mass society, it created new cultural, institutional, and technological contexts presenting new challenges to the position of the arts in Brazilian culture.

It was this period that witnessed a renewed interest in the ideas of Antropofagia, and in the issues of cultural exchanges, cultural autonomy, and cultural conflict. Both the experimental, anticipatory aspects of the Vanguarda Antropofágica (Anthropophagic Avant-garde), and its thesis on cultural autonomy and cultural modernity acquired new relevance, After the “fine arts" Antropofagia began to influence Brazilian theater, cinema, and Popular music. Artists such as José Celso and the Oficina Theater group in drama, Joaquim Pedro in cinema, Caetano Veloso and the Tropicalia movement in popular music utilized the notion of Antropofagia to conceptualize the conundrum of a national, democratic, and popular cultural project facing a new technological modernity of mass-culture values and structures within a peripheral and dependent capitalist society. The notion of Antropofagia allowed the artists to embrace the new technological modernity without renouncing a critical evaluation and critical intervention in the cultural process.

As the Brazilian political crisis of the mid 1960s unfolded, a reactionary, authoritarian political order was being constructed that subordinated economic progress to external control and attempted to control and fashion cultural life to its political interests and doctrines. In such a context, to cannibalize meant to attempt to preserve a sphere of autonomy for the arts by turning into a source of energies the new powers of the masters of mass culture and social domination and the new conflicts and contradictions it introduced and produced in society.

The artist-cannibal explored the cultural conflicts between the “old” and the "new" society, between the conservative culture of authoritarianism and the “free-world” model of a consumer's society with its free circulation of commodities and of commmodified information, and explored also the multiple cultures of the Brazilian world: rural, urban, regional, metropolitan, working- class, aristocratic, middle-class, marginal, native, black, mestizo, Portuguese, African, progressive, conservative, immigrant, oriental, European, modern, ancestral, authoritarian, revolutionary, etc.

The awareness of cannibalism as a strategy of resistance also guided, starting in the 1960s, theoretical interpretations and historical investigations of Brazilian literature, past and present. In the visual arts the marks of Antropofagia could be seen in appropriations by Brazilian artists of American Pop Art themes and style in order to represent the developments of mass culture within a dependent society.

To recapitulate, the Brazilian experience of Antropofagia, that can be seen in the works of Oswald de Andrade, the paintings of Tarsila do Amaral, early Modern and avant-garde art in Brazil to the movies, theater, and popular music of the 1960s and 1970s, anticipated many of the issues of the European-American Post-modernity of the 1980s and 1990s by articulating issues of cultural conflicts, cultural hybrids, cross-fertilization among cultures, cultural resistance, and cultural transformations. Once the “exclusive’ domain of the peripheral artist and the peripheral intellectual, these issues have become pressing questions of the new “globalized” cultural consciousness at the end of twentieth century.

There is much ground for irony in such developments, and that certainly would not have escaped Oswald de Andrade's taste for historical inversions, parody, and paradox. His anthropophagic gesture aimed at setting the stage for the expression of conflict and paradox that structures the cultural self and its self·image. By focusing on the subject of cultural and artistic cannibalism in this period of construction, for better and for worse, of a globalized economy and globalized historical process, the São Paulo Bienal revealed that, ironic and provocative, Antropofagia distills its effects today and shows itself as one of those unavoidable thought- images to which we must constantly, prospectively, return. The anthropophagic thought is perhaps one that, at this point, we can neither conclude nor abandon.

Comments

Post a Comment